If Your Company Does Product Cost Reductions, It's Already Too Late

Product cost, which is roughly equivalent to cost of goods sold on the income statement, is the biggest expense for manufacturing companies, typically 70% to 90% of revenue. You can see COGS as a percent of sales for a random sample of companies in the table below.

Given the magnitude of product cost, one would think that manufacturing companies would have the process of controlling product cost down to a fine art. Sadly, this is not true, and meeting cost targets at start of production in most companies is black art with the predictability of the stock market.

Cost Reduction vs. Cost Avoidance

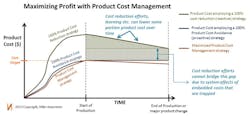

Figure 1 shows a graph of product cost over time in the product life cycle. In the cost reduction strategy, the company goes through product development putting little or no effort into controlling product cost. Cost increases as parts are designed and added to the bill of material. The product is almost assured to exceed its product cost targets at the start of production. After start of production, the cost reduction efforts begin in earnest through a variety of techniques, such as lean, value analysis/value engineering, purchasing demanding year over year cost reductions, etc.

A cost avoidance strategy is exactly the opposite of cost reduction. In cost avoidance, a large amount of effort is spent as early as possible in product development to meet the product’s cost target at launch. However, post launch, little effort is spent on year-over-year savings.

On the graph, we have shown the extremes of the cost reduction vs. cost avoidance strategies. Most companies are doing something in between. However, on which strategy do you think most companies focus? It’s pretty obvious from the graph, correct? Most companies obviously are going to focus on cost avoidance, correct? Right?

Why people reduce cost instead of avoiding it

The sad truth is that most companies focus the majority of the resources they use for product cost control after launch, not before. Why is this? Many who have worked in product development have heard management and others disparage cost avoidance as “not real.” Cost reductions can easily be measured; cost avoidance cannot. For example, I was paying $10 and now I am paying $8. That’s tangible and real. But, if I say, I am paying $7 now, but had I not been careful in my design, sourcing, and manufacturing decisions, I likely would have paid $10, management considers that ephemeral.

This attitude of most management is detrimental to the company’s profit. Can you imagine living your personal lives like this? Let’s say you need to get cable TV service. Would you search around carefully and find the TV channel package you wanted for $60/month? Or, would you do the following: First, do minimal shopping around and take a package for $100/month. Then, a year later, you investigate to find the “low hanging fruit” of a new deal for $90/month. Another year later, you beat on your cable supplier to reduce the price to $80/month. Next year, the “easy wins” are gone, so you really work hard to find a deal for $70/month.

We don’t shop this way in our personal lives, but most companies manage cost in this way. They do it because accountants can measure reductions. Reductions are real. People get rewarded and promoted for reductions.

Why focusing solely on cost reductions doesn’t work

Looking at Figure 2, we can split the difference between the cost reduction line and the cost avoidance line into two parts. The first is the triangular region. Even if, after years of cost reduction efforts, we were able reduce cost to the point at which the cost avoidance line starts at launch, we have still failed. In has taken years to reduce cost, and that triangular region has a name: lost profit.

It is actually worse than this in reality. We will NEVER get down to the same price as the cost avoidance line. We know from the legendary DARPA study from the 1960s that the vast majority of product cost is “locked in” very early in product development. Products are systems, and it’s very hard to extract cost fully without changing the whole system. Furthermore, the cost of making the change is much higher, post launch. Per a 2010 Aberdeen’s study[i], engineering changes made after release to manufacturing cost 75% more than those made before release. These trapped costs that we cannot get out are shown in the rectangular region on Figure 2.

What's the solution? Do both and flip the focus

So far in the article, we have been talking about a 100% cost reduction strategy vs. a 100% cost avoidance strategy. The field of product cost management would teach us to focus on what practically works and generates maximum profit. In this case, the solution is to do the following two things.

- Do BOTH cost avoidance and cost reduction– As shown by the orange line on the graph, the most profit can be made if you meet or come close to your product cost target at start of production and then focus some effort on reduction after launch. Realize that this means that management needs to expect LESS reduction each year in production (e.g. 1% to 2% a year, not 3% to 5% a year).

- Flip the focus of the majority of product cost management resources before production begins– Today 70% to 90% of product cost management resources are focused on reduction. Management needs to flip the focus so the majority of effort is on avoidance.

These improvements require cultural changes in how people are incentivized and motivated. Management needs to cast the vision, educate, and walk the walk. This also requires that companies have a solid process for product cost management. Most do not. A common pit that most companies fall into when attempting this transition is to focus first on hiring more resources or buying software tools, rather than first designing a process and starting cultural change. The right people are critical, and tools can greatly enable the process. However, if the cultural and process elements are not in place FIRST, the company will waste a lot of time and money in failed attempts at product cost management and re-starts to the effort.

These are not easy changes to make, but they are worth the effort.

Consider the table at the beginning of the article again. If your company has 80% cost of goods sold and 5% net margin, then reducing COGS to 79% means a 20% increase to profit! What do you think, managers and executives? Is 20% increase in profit worth the effort? We can ponder that question in another article.

In the meantime, the next time someone disparages cost “avoidance,” show them this article and tell them, “You call it ‘cost avoidance’; I call it maximizing profit.”

[i] “Using Product Analytics to Keep Engineering on Schedule and On Budget,” Boucher, M., Aberdeen, November 2010