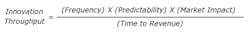

The Growth Equation: Driving Faster Time-to-Revenue for New Products

The previous two articles in this series introduced the levers of Frequency and Predictability as part of the Growth Equation. Now let’s take a look at the third lever—faster Time-to-Revenue.

Time-to-Revenue probably sounds like cycle time to many of you. Cycle time is a component, but the important difference is not just how long it takes you to develop and launch, but how long it takes for that new product to also begin delivering promised sales. If it takes you 9 months to develop and launch a new product and then another 9 months before it begins delivering significant revenue, your development cycle time is 9 months but your time-to-revenue is 18 months.

Naturally some companies, because of their position in the value chain, have longer new product induction periods than others. A chemical additives company may experience a natural induction period where potential customers first formulate and then test in end products. Close partnering to work concurrently with lead or charter customers can certainly reduce induction—but even then only within limits. For instance, if the additive is going into automotive paint, it can take years for the exposure testing alone.

Market & Channel Resistance

The most impactful new products eliminate a problem or reduce a limitation for users. However, one of the challenges of removing limitations is that there may be a vested interest in maintaining the status quo—your new product be damned. Companies, users within companies or even channel partners have invested a lot in finding workarounds and may see change as threatening to their power or position.

As an example of market resistance, a company contacted me about the lack of success they were having with an innovative new fabric ductwork product. It was meant to replace the sheet metal used for HVAC systems. Now why would anyone expect resistance with a product that cost much less, was far easier to use and reduced the requirement for skilled labor? Well, it also challenged the status quo and the myriad of people (union labor, HVAC engineers, building inspectors), policies (building codes, fire codes, etc.), and even agencies involved. They all have something to lose from a move to flexible ductwork, so it would be unreasonable to expect a short or easy induction period. My advice was to look for opportunities in exurban residential or office/industrial park applications where the HVAC infrastructure would not be challenged while continuing to work to educate architects, designers, regulators and other specifiers on the many benefits. That and to look for big downstream buyers that would be willing to push for change in codes and specifications.

The most impactful new products eliminate a problem or reduce a limitation for users. However, one of the challenges of removing limitations is that there may be a vested interest in maintaining the status quo

—Mike Dalton

As far as channel resistance, any new product that isn’t a win-win for everyone in the channel will also struggle to find wide acceptance. Invisalign orthodontics replaced traditional and unsightly (just ask your kids) wires and bands with a series of “invisible” plastic bite plates. Every few months a new set is issued to continue moving the teeth over the course of treatment. When Invisalign initially launched, they sold primarily through orthodontists—the traditional channel for anyone needing their teeth straightened.

Now if you’re an orthodontist with a profitable mid six-figure practice, how excited are you going to be about this opportunity to outsource the differentiated part of what you do? Not very! More likely you’re going to see it as a threat. Eventually, Invisalign got around the resistance with an alternative channel selling through dentists. If you’re a dentist, Invisalign is a new source of income and a complementary way to grow your practice.

You may not face situations as overt as these, but the steps are the same. Look for the norms, policies, regulations, even institutions, that have grown up around the market you are entering. Then brainstorm all the ways they might be threatened and what you can do to reduce the resistance.

Cross-functional Engagement

Cross-functional engagement seems like it should be right up there with motherhood and apple pie, but I often find just the opposite. I’ve worked with several companies where the level of trust between commercial and technical groups was so low that time-to-revenue suffered by anywhere from six months to a year.

In one case, the engineering group for an industrial metering company was notorious for taking shortcuts during scale-up— itself a symptom of poor cross-functional collaboration between design and manufacturing. The sales team responded by ignoring marketing’s launch plans and regularly waiting a year before demonstrating new products to key customers; not an ideal response, but can you blame them for wanting all of the bugs shaken out first?

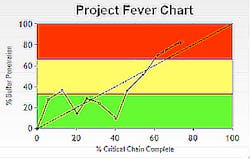

Of course, cross-functional engagement goes well beyond just including all the involved functions in developing the plan. It means regular collaboration and communication that builds trust throughout the execution. It also means transparent communications around issues and problems highlighted by individual project dashboards.

In the next article in the series, we’ll tackle the final lever—Market Impact.

About the Author

Mike Dalton

Managing Director

Mike Dalton is the founder of Guided Innovation Group, where for nearly 20 years he has helped leaders in highly engineered product companies make new products a reliable competitive advantage. He has contributed numerous Industry Week articles and is the author of Unlocking Innovation Productivity and Simplifying Innovation.