Don’t expect to be comforted by reading Rajeev Peshawaria’s new book, Open Source Leadership (McGraw-Hill). Based on a two-year research study, including a survey of 16,000 people, the book finds many of our most common management practices are out of touch with today’s workers, workplaces and society.

Our world is defined by two megatrends, Peshawaria contends: uber-connectivity and uber-population. The internet, mobile phones and other communication technologies mean people are connected all the time with information on nearly everything available to them whenever they want it. This empowers people to an unprecedented degree, he says, and leaves leaders “completely exposed – to the extent of being naked.”

At the same time, the world’s population is rapidly expanding. In 2009, it was 7 billion; by 2100, it may be 10.9 billion. Urbanization is also increasing, with 66% of the global population expected to live in cities by 2050. What this means, Peshawaria writes, is that employers truly have a world of talent available to them and “uber-connectivity will enable them to source talent from wherever it exists.” This allows them, for example, to use open source mechanisms to solicit ideas and push the pace of innovation, often at lower cost than would have been the case with traditional in-house R&D teams.

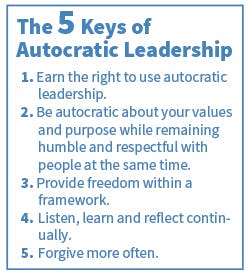

So what type of leadership is needed for this fast-moving, competitive world? Peshawaria says “we’ve been idealizing democratic and all-inclusive leadership far too much, when the need of the hour is – and always has been – autocratic, top-down leadership.” This isn’t an appeal for more bullies in the C-suite. Instead, he writes, companies need leaders to drive results by practicing the “naked autocrat dance,” where they are steadfast about values and purpose but act with “compassion, humility and respect for people at the same time.”

There are plenty of other elements of management dogma that Peshawaria challenges. For example, he argues that stretch goals should not be given to all employees as a way to foster high performance. Applying the 80/20 Pareto rule, he argues that stretch goals only work for the “small percentage of employees [who] have the creativity, innovation and drive to truly relish and achieve stretch goals at any one point or time.” For the majority of employees, he says, stretch goals end up causing “stress, anxiety or poorly thought out behavior.”

Peshawaria also takes issue with the idea that managers have the primary responsibility for motivating their employees. He writes that this idea was born from the 1950s, when jobs were more manual or repetitive and managers served as the resident knowledge gurus for their reports. But for workers who can now tap into the internet on just about any topic, that no longer makes sense.

“The guru is dead, long live Google,” Peshawaria proclaims.

As a result, he says managers should stop trying to motivate employees and start identifying what actually motivates them, fitting that into the overall direction and vision of the company. They should also accept workers’ performance will fall along a 20:60:20 bell curve and realize that along with the high achievers, the “middle 60% and the bottom 20% are also essential to the success of the business, and manage them accordingly.”

About the Author

Steve Minter Blog

Executive Editor

Focus: Global Economy & International Trade

Email: [email protected]

Follow on Twitter: @SgMinterIW

Call: 216-931-9281

An award-winning editor, Executive Editor Steve Minter covers global economic and international trade issues, tackling subject matter ranging from manufacturing trends, public policy and regulations in developed and emerging markets to global regulation and currency exchange rates. As well, he supervises content production of all IW editorial products including the magazine, IndustryWeek.com, research and informationproducts, and executive conferences.

Before joining the IW staff, Steve was publisher and editorial director of Penton Media’s EHS Today, where he was instrumental in the development of the Champions of Safety and America’s Safest Companies recognition programs.

Steve received his B.A. in English from Oberlin College. He is married and has two children.