A Gallup Survey has found yet again that the most engaged work teams "have significantly higher productivity, profitability and customer ratings; less turnover and absenteeism; and fewer safety incidents than those in the bottom 25%."

However, the research organization pegs the cost of disengaged employees in the U.S. at $450 billion to $550 billion.

The assumption is: If employees are disengaged, management will not get their creative, innovative and entrepreneurial power.

Over the last 30 years, corporations have enjoyed record profits and CEOs are making record salaries, but the benefits are not being shared by workers.

Instead worker's wages in most industries have either declined or stagnated.

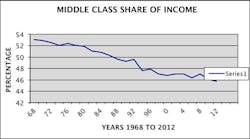

The following chart from the U.S. Census Bureau shows that middle-class income reached a high of 54% in 1968 and declined to 45.7% of total income in 2012.

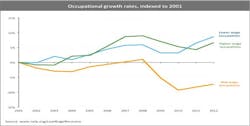

What is disappearing are the jobs in the middle, the good-paying jobs between $14 and $21 per hour with benefits. The following chart, Occupational Growth Rates, graphically shows how the mid-wage occupations are declining and the low-wage jobs have been growing since the beginning of the Great Recession.

The quantity of jobs is not the issue (there will be plenty of jobs). The issue is declining wages.There were—and are—several factors that led to the decline of middle-class income and wages.

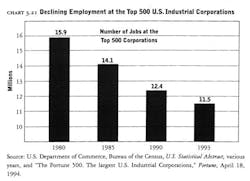

Corporate Re-engineeringAs globalization began to impact the U.S. economy, America’s large corporations began to re-engineer themselves to lower costs any way they could. Primarily, they transformed from vertically integrated companies with all of the functions, departments and people to address all business issues, to lean-and-mean organizations with fewer jobs. Entire departments and business functions were either closed down or outsourced.

This re-engineering included a concerted effort to reduce labor costs in the future, which was felt to be justified by global competition. It started in 1980, and the following chart shows that large industrial companies reduced headcount by 4.4 million in just 13 years.In 2013, the unionized workforce in America hit a 97 year low. Only 11.3% of all workers were unionized. In the private sector, unionization fell to 6.6%, down from a peak of 35% in the 1950s. American corporations have made a concerted effort to eliminate unions and reduce labor costs since 1980—and they have been very successful.

For the past 40 years, manufacturers have made huge investments in automation to reduce labor costs. I was part of this effort when I worked for a company that built robots and palletizer systems. Automation was very successful in eliminating millions of blue-collar jobs. The introduction of the internet and personal computers also gave corporations the opportunity to eliminate millions of white-collar jobs by outsourcing the jobs to Asian countries.

The most insidious strategy to reduce wages was the introduction of the two-tier pay system. Generally, the two-tier pay system rewards long-time employees with keeping their current wages and benefits, but reduces the wages of all new employees. This encourages older union workers to vote against younger workers to maintain their status, which further erodes union solidarity. Over time, as older workers retire and new workers are hired, the overall wage scale of the company declines.

From the union point of view, a two-tier system violates the basic union principle of "equal pay for equal work." But the biggest problem with two-tier pay systems is that they breed disunity, foster unhappiness and produce low morale, because the new worker is doing the same work as another worker and getting only two thirds of his pay. The result is unhappy and disengaged workers.

Since 1980, two-tier wage programs have been used in the airline, construction, chemical, electrical machinery, petroleum, printing, textile, food, transportation equipment, communications, health services, colleges, finance, insurance, steel, aircraft production, tire, wholesale and retail industries.

Many of the jobs that have been created since the beginning of the Great Recession have been part-time or temporary jobs. The Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that part-time or temporary jobs grew from 1.9 million in Jan. of 2010, to 2.7 million in July of 2013. The survey also found that 30% of these people would like to get full-time jobs.

There are several reasons for the surge in part-time jobs. The first is that businesses are still uncertain of the recovery and do not want to hire full-time people only to lay them off if there is a downturn.

The second reason is that consumer demand (measured as consumption) is still too low, and many manufacturing sectors have too much capacity.

Third, it also appears that many small businesses are going to try to keep their headcounts below 50 people to avoid repercussions from Obamacare.

One problem is that part-time and temporary workers usually don’t get any benefits. But perhaps the real downside is that people with these kinds of jobs simply do not make enough money to support a family without using food stamps and other government support.

In addition to part-time and temporary workers there is another growing category called contract workers. These are full-time workers who are self-employed, but not part of the company’s head count. They do not receive benefits and have to pay their own taxes. A good example of contract workers are adjunct professors in colleges.

Contract workers are a relatively new and growing category of employment in the new economy. A research report from University of California finds there are 14.7 million self-employed or contract workers in the U.S., or 10.2% of the total workforce.

Contractors are popular in manufacturing, janitorial services, food service, computer programming, home care services, healthcare and a host of other industries. Contract workers might be the wave of the future as corporations continue to try to reduce their head counts.

The online job site CareerBuilders.com, “cites research that shows 42% of all employers intend to hire temporary or contract workers as part of their 2015 staffing strategy—a 14% increase over the last 5 years.” All of these job categories are contributing to the trend in declining or stagnant wages of the middle class, and disengagement of employees.

Free market capitalists make the case that the market dictates prices and wages based on competition, as well as supply and demand. But with the decline of unions, labor has not been in a position to have much bargaining power since the advent of globalization. So wages have stagnated or fallen, and corporate profits and CEO salaries have reached new heights.

The relentless effort by corporations to reduce labor costs over the last 40 years has been very successful, but it has also created economic problems. Low or stagnant wages have led to lower consumption which has kept GDP growth to a paltry 2%. There is not enough consumption to buy all the goods that America’s factories can produce. All indications seem to show that the labor-cost reduction effort will continue in the future, and there doesn’t seem to be any recognition of what this has done to the middle class.

... how are corporations going to motivate employees to give their best to the company when many of them are living from paycheck to paycheck or living in fear of having their job outsourced?

The irony of this story of decreasing wages and benefits is the anomaly of CEO compensation. A report from the AFL/CIO found that as corporate profits rose, salaries and benefits of CEOs rose from 30 times higher than factory workers in 1980 to 331 times as much as average workers, and 774 times as much as minimum wage earners in 2013. This makes it very tough to convince employees that they must make pay sacrifices to compete in a globalized economy or to convince them there is no income inequality.

A Harvard Business School research survey, found that “71% of survey respondents rank employee engagement as very important to achieving overall organizational success. Yet only 24% say employees in their organizations are highly engaged.” So the big question is how are corporations going to motivate employees to give their best to the company when many of them are living from paycheck to paycheck or living in fear of having their job outsourced?

I think that American corporations know they can be more competitive if they unlock the creativity, innovation and entrepreneurial skills of employees. But motivating them to give their best should begin with a discussion about wages, benefits, security, and inequality.