December 2017 will mark the 10th anniversary of the official start of the Great Recession. During that period of prolonged downturn, the nation lost 8.7 million jobs and GDP contracted by 5.1%.

The recovery period from the financial crisis was long, more so than for a typical post-war economic recession. Data from the government (courtesy of AEI) show that in the expansion phase we finally reached pre-recession levels for output in 2011, a full 30 months after the end of the recession. It took almost three more years – until mid-2014 – for the U.S. economy to surpass its pre-recession workforce peak of 138.4 million jobs.

As anemic as all that sounds, the growth of the overall economy was far more robust than that of the U.S. manufacturing sector.

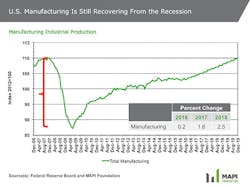

Once the economy bottomed out, manufacturing got off to a faster start than the overall economy: real manufacturing value-added grew 18% in the first five years, compared with 11% for U.S. GDP. Then, in true tortoise-and-hare fashion, the sector hit a wall. And so today, almost a decade after going over the edge, the U.S. manufacturing sector has yet to reach its pre-recession levels of output. MAPI Foundation Chief Economist Cliff Waldman estimates manufacturing production must grow another 6.7% to achieve the December 2007 cyclical peak. At the present pace, the MAPI Foundation’s forecast is for manufacturing not to fully recover until 2019 or beyond.

What’s holding American manufacturers back? Aside from the fact that manufacturing’s contraction was roughly five times that of the overall economy, which meant the recovery had farther to go, a series of headwinds have buffeted the sector. Among those most cited by manufacturers and economists:

- Uncertainty at home. Annual capital investment continues to lag behind the averages of the post-war era, as does R&D investment – two of the most important catalysts for innovation and growth. One reason is that business leaders have entered a prolonged period of uncertainty over many factors critical to such decisions. Chief among these is wondering what federal policymakers plan to do to help or hinder their business strategies. For example, will Congress modify tax policy to encourage repatriation of overseas profits? Will regulations affect companies’ energy production strategies? Business leaders have also been waiting to see if federal and state governments will start investing in our crumbling infrastructure. The list of questions goes on, and so business leaders hold back.

- Stagnant economic conditions abroad. As sluggish as our own economy has been, with 1.5% GDP growth projected for 2016 and a MAPI Foundation forecast of 2.0% for 2017, we appear to be leading the stagnant pack. The World Bank estimates that global growth – including emerging markets – attained a post-recession low of 2.3% in 2016. The European Commission projects 1.7% growth for the euro area in 2016, and Japan likely saw growth of under 1%. China, once the land of double-digit growth, managed output growth of only 6.7%, considered recessionary for that massive market. Add to this the continued strength of the dollar relative to the euro and renminbi, which makes exports more expensive and imports less expensive, and we are left with a large disincentive for businesses and consumers overseas to do business with American companies.

- Collapse of oil and gas prices. As high energy prices can provide a shock to the economy (remember the summer of 2008?), so can the reverse: when prices fall below a certain threshold, companies stop investing in equipment, R&D and people. Energy prices started collapsing in the fall of 2014, and since then – as energy companies experience the deepest price decline in a quarter-century – that industry reportedly has decommissioned two-thirds of its field machinery. This led to sharp declines in exploration and production investment, and those manufacturers supplying the energy industry have seen their world turn upside down, with no light at the end of the tunnel.

Predictions for change in 2017 are mixed. If policymakers in Washington want to end the country’s slow growth prospects, they need to take a closer look at jump-starting the manufacturing sector.

About the Author

Stephen Gold

President and Chief Executive Officer, Manufacturers Alliance

Stephen Gold is president and CEO of Manufacturers Alliance. Previously, Gold served as senior vice president of operations for the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) where he provided management oversight of the trade association’s 50 business units, member recruitment and retention, international operations, business development, and meeting planning. In addition, he was the staff lead for the Board-level Section Affairs Committee and Strategic Initiatives Committee.

Gold has an extensive background in business-related organizations and has represented U.S. manufacturers for much of his career. Prior to his work at NEMA, Gold spent five years at the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), serving as vice president of allied associations and executive director of the Council of Manufacturing Associations. During his tenure he helped launch NAM’s Campaign for the Future of U.S. Manufacturing and served as executive director of the Coalition for the Future of U.S. Manufacturing.

Before joining NAM, Gold practiced law in Washington, D.C., at the former firm of Collier Shannon Scott, where he specialized in regulatory law, working in the consumer product safety practice group and on energy and environmental issues in the government relations practice group.

Gold has also served as associate director/communications director at the Tax Foundation in Washington and as director of public policy at Citizens for a Sound Economy, a free-market advocacy group. He began his career in Washington as a lobbyist for the Grocery Manufacturers of America and in the 1980s served in the communications department of Chief Justice Warren Burger’s Commission on the Bicentennial of the U.S. Constitution.

Gold holds a Juris Doctor (cum laude) from George Mason University School of Law, a master of arts degree in history from George Washington University, and a bachelor of science degree (magna cum laude) in history from Arizona State University. He is a Certified Association Executive (CAE).