US and Mexico – Manufacturing Friends or Foes?

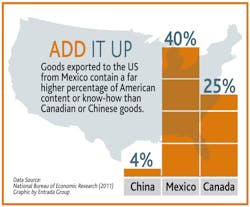

In the ongoing debate within manufacturing about offshoring and reshoring, one statistic speaks volumes. According to a 2011 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research, for every Mexican good exported to the U.S., 40% is of American content compared with 25% for Canadian goods and just 4% for Chinese goods.

That ratio may surprise a lot of people. But it’s essential to remember that the composition of value added to goods exported to the U.S. – whether components, raw materials or engineering know-how – varies tremendously, as this difference between Mexican, Chinese and Canadian production illustrates.

Furthermore, when a U.S-.based company moves production from, for example, China to Mexico, in the vast majority of cases the engineering work is not reshored to Mexico, it’s transferred to the U.S. In this way, the U.S. and Mexico are complementary as manufacturing neighbors.

“The U.S. is unambiguously better off with work coming back from Asia to Mexico than it is with the work staying in Asia,” says Harry Moser, president of The Reshoring Initiative, an organization striving to bring back manufacturing production, and jobs, to U.S. soil. “And there’s some work that is so labor intense that no matter how well you automate, how well you train your team, you cannot justify bringing it back to the U.S. because our wage rates are so much higher.”

What’s in a Number?

Even the experts aren’t fully in agreement about the scope of reshoring. Moser pegs the number of companies that have shifted production to the U.S. from overseas over the last decade at about 500 companies. Meanwhile, Jim Rice and Francesco Stefanelli, of the MIT Center for Transportation & Logistics, recently wrote in an IndustryWeek article that the number is closer to about 50 companies over the last five to seven years.

There is greater consensus around one aspect of the offshoring debate: rising costs in China are causing firms to contemplate a transition to manufacturing in other locations. Fast-growing wage levels, unpredictable transport costs, the rising value of the Chinese currency and an extended supply chain are all factors making Asian-based production less attractive. But if production is leaving China, where is it going?

Mexico as China Alternative

There is a growing willingness on the part of American and Canadian (as well as European) companies to consider Mexico as a manufacturing location from which to export to the Western Hemisphere. The U.S. and Mexico were the only countries to qualify as “Rising Global Stars” in Boston Consulting Group’s (BCG) most recent Global Manufacturing Cost-Competitiveness Index. Proximity to key American and Canadian markets, a young labor force, high productivity per hour, competitive wages and the world’s greatest number of free trade agreements are all key factors in Mexico’s favor, according to BCG.

Similarly, Entrada Group’s own 2014 study revealed that midsize companies that manufacture products for the North American market prefer Mexico or the U.S. as a cost-competitive production location over China by four to one.

Complementary Skill Sets

There are a couple reasons that goods manufactured in Mexico for export to the U.S. have a higher percent of U.S. content than their Chinese counterparts. For starters, skill sets found in American versus Mexican manufacturing are not identical, though there are certainly overlaps. In the U.S., “there are severe shortages [of] toolmakers, precision machinists, welders and [in] other areas,” said Moser. “The various surveys show anywhere from 300,000 to 600,000 openings in manufacturing. [These are] job openings not filled because companies can’t find the people and a lot of it is due to the skill shortage.” Experts like Moser say that while American community colleges, high schools and companies are working to address this gap through education, training and apprentice programs, it will take some time to create enough qualified workers to meet increasing demand.

Second, due to Mexico’s proximity to the U.S., it is usually easier to transport a component to Mexico as part of the production process or even ship a damaged/broken part back to the US for repair than it is to handle such work locally in Mexico. In many cases, the required skill sets in Mexico for mold repair work, for example, just don’t exist. A supplier can have a part shipped back to the U.S., repaired and returned to Mexico within a week. With China, this wouldn’t be possible.

These factors, combined with the equally significant trend of regional production, point to a growing acceptance of Mexico as an alternative to China manufacturing. In the big picture, that is a scenario far more beneficial to the U.S. As Harry Moser puts it: “if you can’t get the work back to the U.S. from China or India and you can get, say, part of it to Mexico and part of it to the U.S., it’s better for the U.S. to be part of the winning team then all of the losing team.”

There are many ways that manufacturers in Mexico and the U.S. are working together, including foreign direct investment (on both sides), joint ventures, new sales and distribution offices, and research and development centers sharing information between the two countries. While it’s evident that the modern manufacturing environment and globalization has forever changed the industry as it operated for decades, it’s ultimately important to not lose sight of the fact that global production, on the whole, continues to rise and create opportunities for companies seeking entry to new markets.

Doug Donahue is Vice President of Business Development with Entrada Group, a U.S.-based company that offers small-to-midsize manufacturers expanding to Mexico a proven, turnkey system for long-term growth.