Is Reshoring Really Working?

Are manufacturing companies and operations coming back to the U.S.? Yes, in some cases. Are they bringing back jobs? Yes, but not enough to counter what has been lost. Could this economic tide change radically? Some believe it could with the right national policies.

A number of studies circulating suggest that companies plan to reshore manufacturing operations to the U.S. A new Michigan State study, for example, said 40% of manufacturing firms surveyed believe there is increased movement of production back to the U.S. The sample size was just 319. Other studies predict huge job gains. A survey by the Boston Consulting Group is touting job gains of 2.5 million to 5 million based on costs advantages that will shift in favor of U.S production. While these might be indicators of future behavior, for now it’s a mixed bag when looking at the impact of the reshoring that is currently taking place.

See Also: Manufacturing Plant Site Location Strategies

Why are companies coming back? Some cite the increase in the cost of labor in China that has made offshoring to China less of a bargain than it once was. Other reasons given for returning to the U.S. include transportation costs, supply chain issues, lead times, quality and intellectual property protection. Another factor, say some observers, is that manufacturers are now assessing their costs more completely and finding the numbers favor a U.S production base.

Some manufacturers are bringing back specific lines while others are turning to domestic suppliers. Often new jobs are created, but not always. GE (IW 500/5), for example, is building up its appliance business in the U.S. with new plants and lines, adding 1,300 new jobs by 2014. But in the case of tool maker Channellock, a component returned to the U.S., but jobs weren’t added.

Still, the big question that looms over reshoring is whether or not it will result in the replacement of the 5.5 million manufacturing jobs that were lost in the last decade.

One example of a company that is on both sides of reshoring is Whirlpool (IW 500/63). The company has both closed factories in the U.S. and is reopening plants as well as bringing back products to be manufactured in the U.S.

“Whirlpool has complete confidence in the competitiveness of U.S. manufacturing, which is evident by the fact that we have been investing and growing here for 101 years,” Jeff Fettig, chairman and CEO of Whirlpool Corp., told INDUSTRYWEEK.

The company’s investment in its U.S. footprint, which began in 2010, will reach $1 billion by 2014.

“We look at ‘best cost’ as opposed to ‘low cost’ when deciding where to make manufacturing investment, from design to manufacturing to delivery into a consumer’s home,” he added. “That broader perspective, along with true, consumer-relevant innovation, has enabled us to continue to lead the global appliance industry and employ more U.S. manufacturing workers than all of our competitors combined.”

The company, which employs 22,000 workers in the U.S., points out that 80% of the products it sells in the U.S. is made here. And by next year 100% of its large residential washing machines will be manufactured stateside.

Interestingly, the company doesn’t use the word reshoring to describe the process of bringing operations back to the U.S. “We call it upshoring,” says Jeff Noel, vice president of communications and public affairs for Whirlpool. “We never really left the U.S.”

He explains that often the company begins manufacturing a product outside the U.S. with the intent to bring it back to the states if the product captures a strong market share in the United States.

Whirlpool’s belief in the strength of the U.S. market, despite higher rates of growth in other regions, is the reason the company has committed to a number of U.S. investments including $120 million for a new cooking products plant in Tennessee adding 130 jobs, $200 million in an Ohio laundry facility adding 50 jobs, $20 million in a refrigeration plant in Iowa and an $18.6 million outlay in a Michigan design facility.

The company also acquired the former WC Wood facility in Ottawa, Ohio, adding 400 jobs and bringing total employment in Ohio to approximately 10,000, making it the largest manufacturing center for appliances in the United States.

However, the company also closed a plant in Iowa in 2008 due to decreasing demand for the refrigerator model produced at that plant and laid off 400 employees. And in 2012 the Fort Smith plant in Arkansas was closed due to weak demand and rising material costs, accounting for a total job loss of 1,000.

A Question of Job Creation

Viewing the success of reshoring from the perspective of job generation is difficult, as there are no official numbers. While manufacturers have added a half-million new U.S. workers since 2009, it remains unclear how many of these new jobs are due to reshoring.

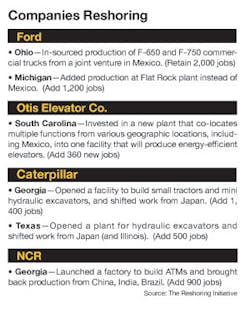

However, some sectors are bringing jobs back in strong numbers. The auto sector is a good example. Ford is investing $16 billion in its U.S facilities, resulting in 12,000 new jobs by 2015. The company has already brought back operations from Japan, Mexico and India.

The sector saw strong capital investment last year of $13.09 billion. And there has been significant job additions. According to the U.S. Commerce Department, the auto industry and parts sectors have added 165,000 jobs since June 2009. Still, they haven’t been enough to replace all the jobs lost in the recession. According to a Jan. 3, 2013, report by the Center for Automotive Research, the “recovery in automotive employment is slowing and may not reach pre-recession levels.” The group forecasts that the industry will add 90,000 employees by 2016, of which about one-third will be in motor vehicle manufacturing and two-thirds will be in the automotive supplier sector.

While automotive employment may not fully recover, production is expected to reach pre-recession levels by 2015 due in part to favorable conditions in the U.S. Two phenomena account for this upsurge, explains Greg Burkart, managing director with Duff & Phelps. “One phenomenon is regional manufacturing strategies that are being developed which improve supply chain efficiencies, in turn creating a reason to produce cars domestically.”

The other phenomenon is that the "U.S. is becoming a more competitive exporting base due to increases in productivity as well as favorable exchange rates," Burkhart says. This accounts for capital investments in 2011 by Toyota, Daimler, Honda, Nissan and BMW.

While the auto industry is adding jobs, in part due to reshoring, not all reshoring results in additional jobs.

Channellock, a manufacturer of hand tools, produces most of its lines in Meadville, Pa., with a small percentage of manufacturing occurring overseas. For one particular line, called Code Blue, the supplier of the grip had a plant in Taiwan. When that plant closed, CEO William S. DeArment was sure he could find a comparable part in his hometown as the area is well known for its tool and die expertise. He did, and now the product is 100% made in America. However, the domestic sourcing did not result in additional jobs.

While all of his products carry a "Fiercely Made in the USA" tag, DeArment believes it’s the quality of U.S.-made products that draws consumers, not the location of the factory. "In the tool and die industry companies are coming back because the quality of this industry in the U.S. is stronger," DeArment says.

The New Role of Energy

In addition to quality, a new supply of affordable energy, in the form of shale gas, could play a significant role in pulling manufacturers back to the U.S., according to Bob McCutcheon, U.S. industrial products leader at PwC. "The significance of the abundance of this resource is undeniable," McCutcheon says. "And we need to find a way to have agreement on how to extract this resource."

The firm predicts $11.6 billion in energy cost savings by 2025, based on high shale gas recovery scenarios resulting in increased consumption of cheaper natural gas.

The production of a stable supply of shale gas would enable manufacturers to enjoy lower feedstock and energy costs. Chemical companies are already increasing investment in the U.S. as they seek cost advantages by using cheaper ethane, thus becoming more competitive than companies that rely on oil-based naphtha, McCutcheon reports. How many jobs this will bring back is a matter of debate.

While energy cost is one important factor, affecting certain industries more than others, all manufacturers need to manage supply chain costs. "One of the biggest reasons companies have come back to manufacture in the U.S. is the need to quickly meet market demand," says John Zegers, director of the Georgia Center of Innovation for Manufacturing, Georgia Department of Economic Development.

Moreover, says Zegers, local sourcing is an important component of successful innovation. "OEMs are using job shops in the U.S. to innovate," he observes.

Trying to quantify the cost advantages of either energy, lead time, or other issues such as intellectual-property protection, in determining plant location is difficult.

"Most companies make sourcing decisions based on price alone, resulting in a 20% to 30% miscalculation of actual offshoring costs," explains Harry Moser, president of the Reshoring Initiative, a group he founded in 2010 in an effort to bring back jobs to the U.S.

"Companies looked mostly at labor costs when deciding whether to move offshore," Moser adds. "They weren’t focused on other costs such as intellectual property, import/export costs and potential shortages against demand because of unpredictable variables like shipping."

So his group developed the Total Cost of Ownership Estimator that incorporates 29 cost factors. Moser believes that if companies correctly applied this calculation, it would bring back 1 million U.S. jobs. If other factors were considered, such as better training, process improvement, automation, wage parity with China, and offshore currency manipulation stopped, Moser says the U.S. would add 6 million jobs.

Policy Actions Needed

Robert Atkinson, president of the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, a Washington, D.C., think tank, cites currency manipulation as one economic factor that is holding back more dramatic expansion of U.S. manufacturing. In fact, he says, "If we put more pressure on China and the yuan increased 20% or 30%, this would have a global effect."

The effect of an undervalued yuan on trade has Scott Paul, president of the Alliance for American Manufacturing, upset as well. "We should demand action from the administration and World Trade Organization when trade cheats like China illegally subsidize competitive industries and manipulate their currency to artificially cheapen their exports," he declared in a recent op-ed in USA Today.

Another public policy issue that affects location decision is U.S. tax policy. As of 2011 the U.S. had the highest corporate tax rate in the world. "We need to have a more competitive tax code," Atkinson said.

DeArment of Channellock agrees. "What would help encourage even more companies to come back, "says DeArment, "are better tax policies. There is no growth incentive in the tax code. Consumption is rewarded while production is penalized."

Achieving that might not be so easy, Atkinson concedes, but his organization is calling on the U.S. to adapt a tax device called a "patent box" that many countries are using to bolster their competitiveness. A patent box significantly reduces the corporate tax rate on revenue from qualifying intellectual property, based in part on the extent to which corresponding R&D and production is conducted domestically.

While public policy issues are debated, market factors seem to be pointing toward reshoring, and companies such as Whirlpool are pushing for domestic production. In a recent speech, Fettig said he doesn’t buy claims that companies can’t manufacture their products cost effectively in the United States. He believes the offshoring storm has calmed and expects to see some operations continue to shift back to U.S. soil.