World's Biggest Shipping Firm Warns Against US Protectionism

A. P. Moeller-Maersk A/S, a Danish conglomerate that owns the world’s largest container shipping company, is voicing concern as a potential shift in U.S. policy threatens to reduce global trade.

While Maersk assumes that no matter how the U.S. presidential election ends, it probably “won’t have an effect on the contracts we have and the employment exposure we have in the U.S.,” Trond Westlie, its chief financial officer, said any steps in a more protectionist direction would clearly hurt global economic growth.

“In general, trade barriers weaken global growth,” Westlie said in an interview on August 13. “Low trade barriers not only help trade growth, but also economic growth.”

With real-estate-magnate-turned-politician Donald Trump blaming China and Mexico for American job losses, the tone in the U.S. presidential race is more anti-trade than it’s been in decades. Democratic party nominee Hillary Clinton is also toughening her stance on globalization, and has criticized the Trans-Pacific Partnership for failing to do enough to support American jobs. Trump has gone so far as to call the pact a “disaster” for the U.S.

Westlie declined to comment on either candidate or on any specific elements in their proposals as they vie for the presidency. But the government in Maersk’s home country of Denmark has been less restrained in voicing its concerns. Foreign Minister Kristian Jensen says he’s “worried about what Trump has said.”

There are two things “in particular” that are grounds for unease, according to Jensen. “His anti-trade rhetoric” is one, while “the second issue is his security and defense policy, where he’s questioning NATO’s Article 5,” the minister said in an interview.

Trump has implied NATO members would only get U.S. assistance if they paid for the favor, while he has flirted with Russian President Vladimir Putin without providing much insight into how he would shape U.S.-Russian relations in practice. All the same, if U.S. voters end up making Trump their president, “we will find a way to work with him,” Jensen said.

The World Bank has identified trade as a key means to fight poverty. But since the global financial crisis, cross-border commerce has slowed, and in a report this year, the World Trade Organization estimated that trade grew less than 3% for a fifth consecutive year. It cited the “threat of creeping protectionism as many governments continue to apply trade restrictions,” in an April 7 report. Trade growth will reach 3.6% next year, compared with a 5% average since 1990, according to the WTO.

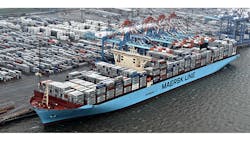

Maersk transports about 15% of the manufactured goods that are sent across the globe each year, making it the world’s biggest container shipping line. Maersk Line lost $151 million last quarter, down from a profit of $507 million a year earlier, as freight rates plunged 24%.

Maersk and others in the shipping industry have been pummeled by the fallout of overcapacity just as the global financial crisis hit. A global wave of protectionism threatens to exasperate the situation for an industry already struggling to turn a profit.

“Trade barriers should be reduced as much as possible,” Westlie said. “That opinion stands whether we’re talking about Brexit or the U.S., but also for tariffs in Africa or South America, for example. So it counts for all countries, not just individual ones.”

By Christian Wienberg

About the Author

Bloomberg

Licensed content from Bloomberg, copyright 2016.