This article is not about lean manufacturing.

It’s about the assumption plant operations make when they implement lean strategies to purge waste in pursuit of customer value -- the assumption that the manufacturing lines are actually running and products are actually being produced.

Downtime is the enemy of lean. Downtime is, in fact, waste.

Idled lines do not add value. Restarting production after unplanned downtime requires more effort, usually expended with less efficiency and worker productivity. This reintroduces waste, which creates added costs that customers do not pay for, yet must be absorbed into cost of goods sold.

With this at stake, implementing IT strategies that reduce or eliminate unplanned downtime of critical manufacturing applications should be integral to lean program strategies. This often requires a change in mindset.

Most IT and operations people prepare for rapid recovery from failure, assuming it is inevitable. Instead, proactively preventing downtime from happening in the first place yields better outcomes; it’s also more efficient in practice and cost-effective over the long term.

Further, most organizations -- manufacturing or otherwise -- do not know the real cost when downtime strikes critical applications. Without knowing the value of downtime, the ability to choose the correct technology to protect the applications you need most, and weighing the risk/benefit of each choice, is suspect.

A Greenfield Opportunity

Is unplanned downtime a way of life for manufacturers or a target-rich area for new lean initiatives?

Consider this: A survey conducted by IndustryWeek magazine of 500 subscribers (sponsored by Stratus Technologies) found that manufacturers had unplanned downtime an average of 3.6 times annually. Nearly one out in three experienced an outage in the first three months of 2012.

The survey also found that two out of three manufacturers have no strategy or IT solutions for high availability in their plants. The downtime-recovery choice for 64% of respondents is passive back-up, the least effective method shy of doing nothing at all.

In that same survey, respondents estimated their downtime cost per incident. The composite average was approximately $66,000 annually. For manufacturers with revenues above $1 billion per year, the average cost was more than $146,000 spread across an average of 4.5 annual downtime incidents.

In our experience, these average cost estimates are low, which often happens when you directly ask the question without additional probing into factors behind the answer. Many professional research firms and industry consultants do conduct in-depth analysis of downtime costs. Cross-industry estimates range from $110,000 to $150,000 per hour and higher for the average company.

A 2010 study by Coleman Parkes Research Ltd, on behalf of Computer Associates, pegged the average cost for manufacturing companies specifically at $196,000 per hour. That same research found that the average North American organization suffers from 12 hours of downtime per year with an additional eight hours of recovery time; numbers are slightly higher for European firms. Two thousand organizations participated in the survey.

Calculating Downtime Cost

Determining the total of hard and soft downtime costs is not easy, which is why it’s often not done well if at all.

One would think that tallying direct wage cost absorbed during an outage would be a simple matter. When is an outage over? When the problem is fixed or when full production is resumed? Employees do not immediately return to full productivity during the recovery period, and may not for hours; the full value of their labor is not being realized.

Work in process may need to be discarded, as may work produced during the recovery period that doesn’t meet specifications. The line can lose sequence, generate a lot of scrap, or even damage tools because systems recover to an unknown state. You may incur repair costs and outside service expenses. Internal IT resources are diverted from doing something else to fix your problem.

Highly integrated systems can push the effects of downtime on the production line to administrative functions upstream and down, into the supplier pipeline, to customer order fulfillment and product delivery. Downtime can invoke financial penalties if contract conditions are breached, or if regulatory requirements are violated. Customer relationships get damaged and reputations tarnished.

All these, and many other variables particular to your own manufacturing processes and environment, are legitimate contributors to the cost of downtime and should be included.

Availability Options

Some production-line applications are more critical than others. The first applications you want back online usually are the ones that need higher levels of uptime protection.

A full analysis of availability products, technologies and approaches is beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say, each has its place, its benefits and tradeoffs, and very real differences in the ability to protect against application downtime.

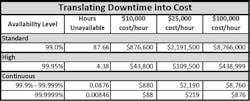

A common way to assess a solution’s efficacy is by looking at its “nines,” i.e. its promised level uptime protection. The chart below shows the expected period of downtime for each level, and how that might translate into financial losses. Note that downtime per year could be a single instance, or spread across multiple incidents. Also note that higher uptime does not necessarily mean a solution is more costly; software licensing, configuration restrictions, required skills, ease of use and management are just a few of the many factors affecting total cost of ownership.

As we mentioned at the outset, most high-availability solutions focus on recovery after failure. Very few are engineered to prevent failure from occurring.

Virtualization

The benefits of virtualization are indisputable. More and more manufacturers are using virtualization software on the plant floor to consolidate servers and applications, and to reduce operating and maintenance costs. Some rely on its availability attributes to guard against downtime, as well.

By its nature, virtualization creates critical computing environments. Consolidating many applications onto fewer servers means that the impact of a server outage will affect many more workloads than the one server/one application model typically used without virtualization. The software itself does nothing to prevent server outages, and you can’t migrate applications off a dead server.

Restarting the applications on another server takes time, depending on the number and size of applications to be restarted. Data that was not written to disk will be lost. The root cause of the outage will remain a mystery. If data was corrupted, then corrupted data may be introduced to the failover server.

This may not pose a problem, depending on your tolerance for certain applications being offline for a few minutes to an hour, perhaps more. However, many companies are reluctant to virtualize truly critical applications for this reason. High availability software and fault tolerant servers are viable options to standalone servers, hot back-up or server clusters as a virtualization platform, and worth evaluating. These technologies are sometimes overlooked because of a lack of familiarity, or outdated notions that they are complex or budget-busters.

Summary

Manufacturers are squeezing more efficiency, productivity and value out of existing resources by using lean manufacturing techniques. IT systems downtime derails these initiatives by reintroducing cost, production inefficiencies, lost customer value … i.e. waste. Preventing downtime from occurring is a more efficient, effective strategy than recovering from failure after it has occurred. Determining the cost of downtime is a necessary step to evaluating which applications require the greatest protection against downtime. Only then can appropriate availability technologies and products be chosen based on need, available resources to manage them, and ROI.

Frank Hill is the director of manufacturing business development for Stratus Technologies. Prior to joining Stratus, Mr. Hill led MES business development at Wyeth, Merck & Co., and AstraZeneca for Rockwell Automation. He has also worked in manufacturing leadership at Merck & Company. He is a frequent speaker and commentator on technology-enabled manufacturing solutions.